Troubleshooting Boring Operations

As suggested earlier, a variety of factors determine whether a boring operation is predictable and productive. Unfortunately, this can make boring seem like a black art, but it’s really not. By following the guidelines provided so far, boring shouldn’t be more difficult than any other type of machining. And when trouble does arise (as in chatter or problems with tool life and hole accuracy), here are a few tips to get things back on track.

- Play with the feeds and speeds. Try reducing the cutting speed, increasing the feedrate, or vice-versa. But be scientific about it. Adjust one variable at a time and only by a small amount—say 10% either way—and then document the results. If they were poor, put the value back and try a different one. Continue optimizing in this manner until you obtain the desired results.

- Another variable is depth of cut (DOC). For a finishing pass, a good starting point is a DOC equal to or greater than the tool nose radius (TNR). If this is too heavy, try using a smaller nose radius. For rough boring, taking lighter cuts (say several times the nose radius) at slightly higher feedrates is usually preferable to “hogging” passes. Again, play around until you find the right balance of cutting forces, chip control, and vibration dampening.

- Is the part secure? If it's hanging a long way out of the chuck or not adequately gripped in the vise, chatter will rear its noisy head. Tubing and other thin-walled workpieces can also be problematic. If conditions permit, try taking a heavier DOC on the finishing pass, or bury the part deeper in the workholding device.

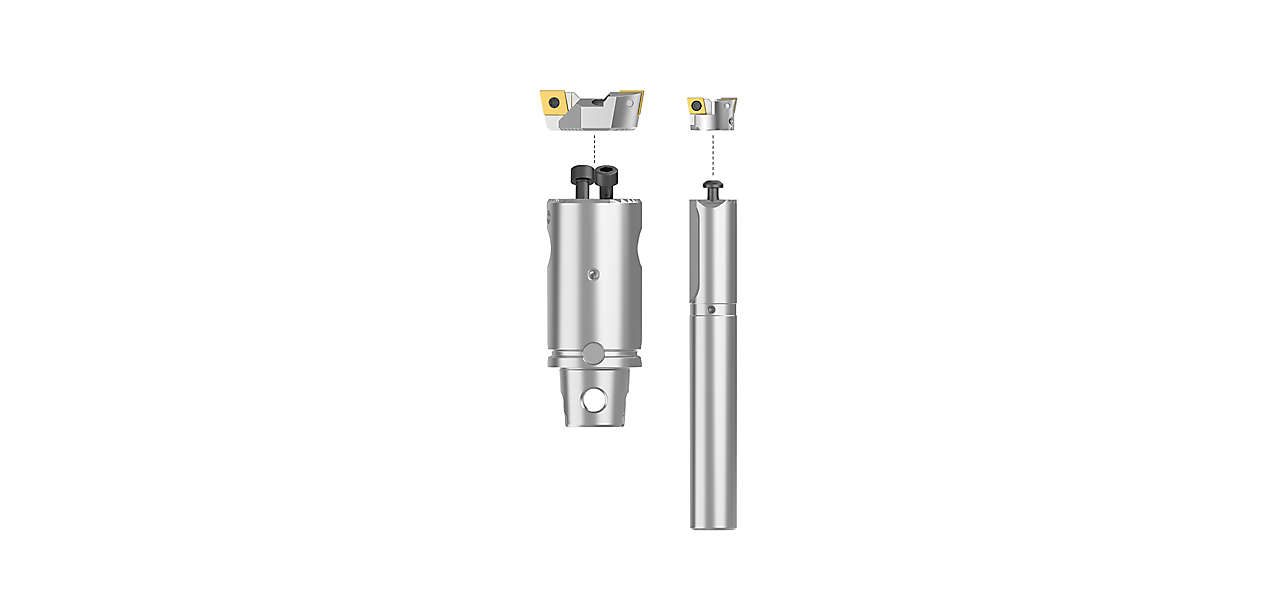

- We already noted the importance of minimizing boring bar stick-out, but equally important is how much of the bar you should be hanging on to—shoot for at least 4x the bar diameter, more if possible. Also, avoid clamping the bar with set screws. A sleeve or collet that wraps completely around the shank will provide a more secure grip.

- It only makes sense to use the largest boring bar for the hole, as this will create the least deflection. However, there must be room for effective chip evacuation. If not, chip packing ahead of the cutting zone is a near certainty, leading to disastrous results. With this comes the need for generous application of cutting fluids, preferably using high-pressure coolant (HPC).

- Some CNC machine tools offer a feature known as spindle speed variation, or SSV, which as its name implies, dynamically varies the spindle speed according to a set of predefined parameters. For example, machines from Haas Automation have two options—M38/M38 and M138/M139—that adjust the RPM based on machine settings or program variables respectively. Either can be effective against chatter.

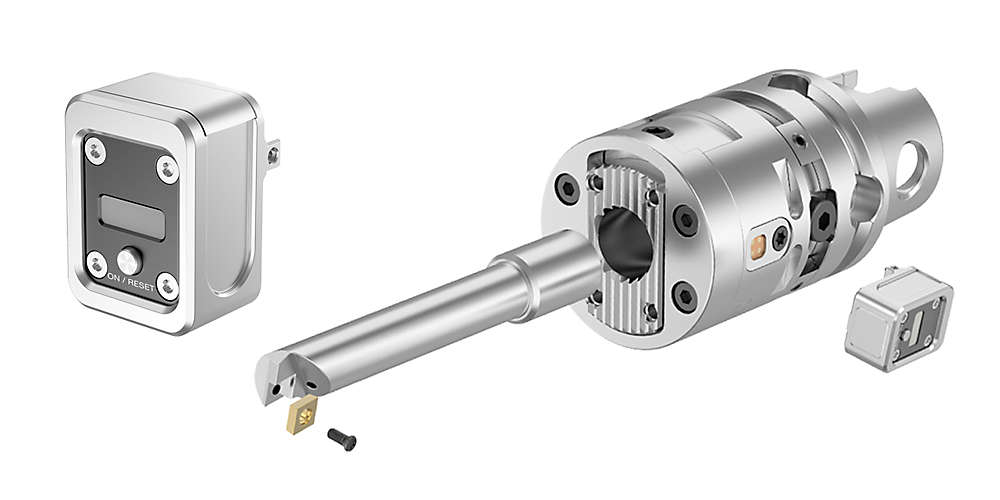

Finally, boring bar alignment is critical. The tooltip should sit perfectly on the hole centerline or perhaps a ‘thou or two above center to allow for deflection. Most bars have a flat ground on the top that simplifies this process, but what happens if the machine is out of alignment or you’re gripping the bar with a sleeve as suggested a few bullet points ago?

Several solutions are available. For CNC lathes, a digital alignment tool (Wixey brand is one) works well on larger bars. With smaller tools or when you want to go old school, clamp and face off a piece of bar stock, paint some Dykem bluing fluid on the end, and then use the machine's manual pulse generator to scribe a line across the face with the boring bar tip. This will provide a measurable indication of the bar’s alignment. On CNC machining centers, the process is even easier—just use an offline tool presetter (assuming your shop has one) or optical comparator to set the tool on center. Either way, accurate and productive boring is within reach.