What is Peripheral Milling?

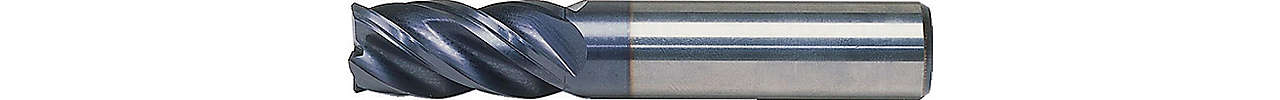

Face milling’s counterpart is peripheral milling. Ironically, it uses an end mill or sometimes a shell mill, even though most of the material removal occurs on the cutting tool's sides, or flutes. If you’ve never seen one, an end mill looks a lot like a drill bit. Both have helical flutes (usually), except that an end mill is flat at the end rather than pointed like a drill. Also, drills typically have only two flutes, whereas end mills often have four or more.

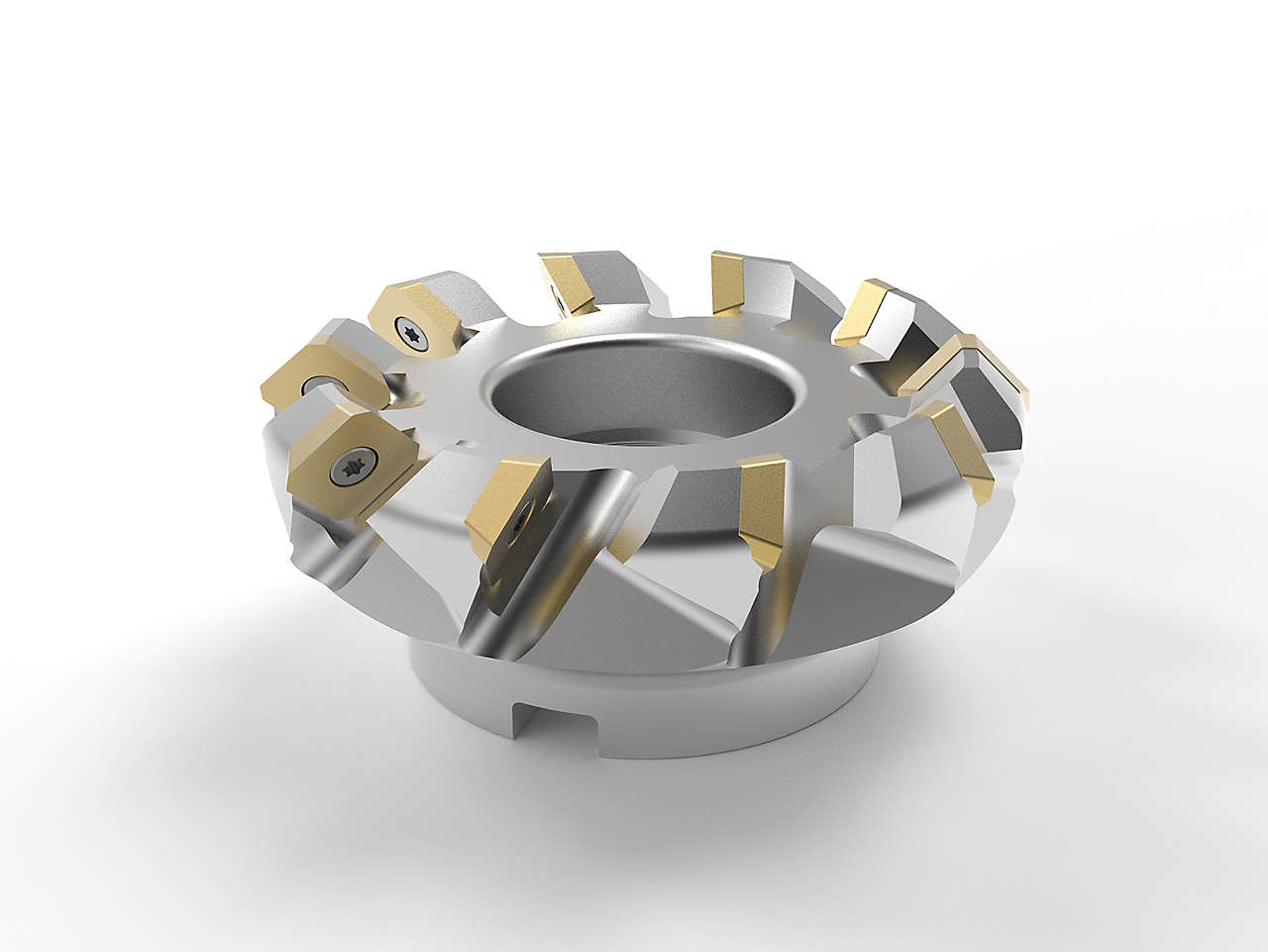

Where a face mill removes material from the workpiece’s top surface, an end mill (and its larger cousin, the shell mill) removes it from the part’s periphery, as well as from the inside of a pocket (or pockets) within the part. Depending on the milling strategy, the tool is positioned to a predetermined depth (again, in the Z-axis) and then fed into and around the workpiece until complete. As with face milling, success with peripheral milling depends on the right feedrates and cutting speeds, appropriate depths of cut, and adequate machine power and clamping force.

It should also be noted that an end mill can be used to perform face milling, albeit not as efficiently as a face mill. For example, the bottom of the pocket just mentioned must be machined flat, and since face mills are generally too large to fit inside a workpiece, an end mill is the only option. Also, most face mills (though not all) cannot machine a square shoulder, so once more, an end mill or shell mill must be used.

Finally, ball-nosed and radiused end mills are typically used to machine the inside surfaces of mold cavities and other three-dimensional shapes. A face mill, by contrast, can only machine flat surfaces perpendicular to the axis of the machine spindle. More than any other factor, this perpendicularity defines the difference between peripheral milling and face milling—where the latter is always at a right angle to the spindle, peripheral milling or end milling is always done in a parallel direction.