What is Tapping?

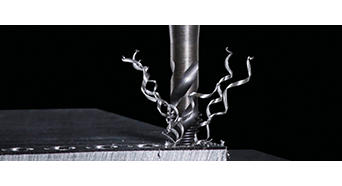

At first glance, a tap looks quite similar to a bolt or screw, albeit one with grooves running down the sides. These grooves are used to conduct chips up and out of the hole during machining, just as the sharp edges on the end and periphery are used to cut the threads. Taps work much like any other rotary tool, in that they’re gripped in a chuck, collet, or special “floating” toolholder (more on this shortly) and then driven into the workpiece at a specific feedrate.

The two caveats to this are as follows: there must be a hole slightly larger than the thread’s minor diameter (taps are not drill bits and only cut on the tool's outer edges), and the feedrate must be precisely equal to the thread’s pitch—a 1/4"-20 tap, for example, must advance 0.05" per revolution (or 20 threads per inch) to produce a good thread.

Just as there are many different types of threads, so does a wide variety of taps exist. Plug taps are generally used to thread “through-holes” while bottom taps are as their name describes, able to produce threads up to the very bottom (almost) of blind holes. Spiral point taps tend to drive chips forward, whereas those with spiral flutes direct them upwards, out of the hole.

There are also forming or roll taps, which produce no chips at all. Instead, they displace material, much like the thread-rolling process mentioned in the introduction. These follow the same basic rules as cut taps insofar as feedrate and tool geometry, but require a slightly larger pilot hole to allow for the displaced metal. However, form taps are limited to ductile materials like aluminum, stainless steel, and superalloys, and should not be used with cast iron or hardened steels.